Quand le langage vous oblige à préciser si vous l'avez vu vous-même

Résumé: Cet article explore le concept linguistique fascinant d'évidentialité. Nous nous penchons sur des langues comme le tuyuca et le tariana, qui exigent une preuve de connaissance dans chaque phrase.

Annonces

Vous découvrirez comment ces structures grammaticales influencent la vérité, la confiance culturelle et le traitement cognitif à l'ère moderne.

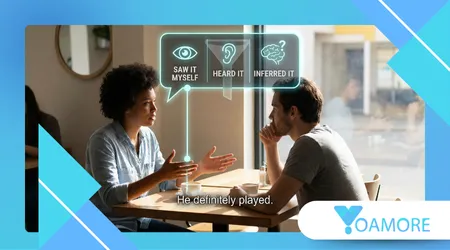

Imaginez une réalité où l'on ne peut pas simplement énoncer un fait sans justifier grammaticalement sa source. Dans certaines cultures, La langue vous oblige à mentionner si vous l'avez vu vous-même. avant de terminer votre phrase.

Ce concept, que les linguistes appellent l'évidentialité, modifie fondamentalement la façon dont les humains partagent l'information. Il ne s'agit pas simplement d'honnêteté ; c'est une exigence structurelle inscrite dans la syntaxe même du langage courant.

Les anglophones prennent souvent la liberté d'affirmer des faits sans citer leurs sources. On peut dire « Il pleut », que l'on soit dehors, devant une fenêtre, ou en train de consulter une application.

Annonces

Cependant, pour les locuteurs de certaines langues autochtones d'Amazonie, une telle ambiguïté est grammaticalement impossible. Il faut préciser si la pluie est quelque chose que l'on voit, que l'on entend, ou que l'on suppose simplement.

Cette obligation linguistique crée un système de vérification intégré à la communication. À l'ère de la désinformation numérique en 2026, ces structures grammaticales anciennes offrent de précieux enseignements sur la responsabilité et la vérité.

+ Comment les langues des signes créent des règles grammaticales entièrement nouvelles

Qu’est-ce que l’évidentialité en linguistique ?

L'évidentialité est une catégorie grammaticale qui indique les preuves à l'appui d'une affirmation. Elle oblige le locuteur à expliciter, au sein même du verbe ou de la structure de la phrase, comment il sait ce qu'il prétend savoir.

La plupart des langues, y compris l'anglais, expriment cela de manière facultative par des moyens lexicaux. Nous utilisons des expressions comme « j'ai entendu dire », « apparemment » ou « il semble » pour nuancer nos propos lorsque nous le jugeons nécessaire.

En revanche, l'évidentialité grammaticale rend cette spécification obligatoire. Il est impossible de former une phrase grammaticalement correcte dans ces langues sans choisir le suffixe approprié pour indiquer la source d'information précise.

Les linguistes classent ces systèmes selon la complexité des distinctions qu'ils établissent. Certains systèmes sont simples et ne font la distinction qu'entre preuves directes et indirectes, tandis que d'autres sont extrêmement précis et nuancés.

Cela oblige l'orateur à évaluer constamment la qualité de ses connaissances. Avant même que les mots ne sortent de sa bouche, son cerveau doit catégoriser l'expérience comme visuelle, sensorielle, inférée ou rapportée.

+ La boussole culturelle : décrypter les mots intraduisibles les plus étranges du monde entier

Quelles langues exigent une preuve stricte de la source ?

Les exemples les plus célèbres d'évidentialité complexe proviennent de la famille linguistique tukanoane. Ces langues sont principalement parlées dans la zone de frontière floue entre le Brésil et la Colombie, au cœur de la forêt amazonienne.

Le système de Tuyuca est souvent cité comme l'un des plus exigeants. Il utilise cinq paradigmes distincts pour classer les preuves, ne laissant absolument aucune place aux affirmations vagues ou aux rumeurs non vérifiées.

Un autre exemple notable est le tariana, une langue arawak parlée dans la même région. Les locuteurs du tariana considèrent l'emploi abusif des marqueurs évidentiels non seulement comme une erreur grammaticale, mais comme un mensonge grave.

Utiliser le mauvais suffixe peut vous faire passer pour quelqu'un de peu fiable, voire délirant. Prétendre avoir vu quelque chose alors que vous l'avez seulement entendu constitue une violation du contrat social fondamental.

Ces langues ne sont pas des vestiges du passé ; ce sont des outils de communication sophistiqués. Elles privilégient la validité de l’information à la rapidité de sa transmission, un concept qui paraît révolutionnaire dans notre monde trépidant.

Pour en savoir plus sur la diversité des structures grammaticales et l'évidentialité, cliquez ici.

Comment Tuyuca structure-t-elle la réalité ?

Les locuteurs du tuyuca doivent ajouter des terminaisons spécifiques aux verbes pour indiquer leur provenance. Par exemple, la phrase « Le garçon a joué au football » change complètement selon la présence physique du locuteur lors de l'événement.

Si vous avez vu le match, vous utilisez une preuve visuelle. Si vous avez entendu les cris mais n'avez pas vu le ballon, vous devez utiliser une preuve sensorielle non visuelle.

Le tableau ci-dessous illustre les cinq catégories utilisées en tuyuca. Cela démontre la précision requise pour une simple phrase comme « Il a joué au football » (en utilisant la racine). bíi-).

| Type de preuve | Exemple de suffixe | Signification / Contexte |

| Visuel | -je | Je l'ai vu jouer au football. |

| Non visuel | -gi | Je l'ai entendu jouer (mais je ne l'ai pas vu). |

| Apparent | -híyi | Je vois des preuves qu'il a joué (par exemple, des crampons sales). |

| D'occasion | -yigɨ | Quelqu'un m'a dit qu'il jouait. |

| Supposé | -híyiki | Il est raisonnable de supposer qu'il a joué. |

Ce système lève toute ambiguïté quant au point de vue de l'orateur. On sait immédiatement s'il s'agit d'un témoin oculaire, d'un colporteur de rumeurs ou d'un enquêteur déduisant des faits à partir d'indices.

Pourquoi cette distinction est-elle importante en 2026 ?

Nous vivons à une époque où la frontière entre faits et opinions est dangereusement ténue. La langue vous oblige à préciser si vous l'avez vu vous-même. Dans ces cultures, il s'agit de créer une barrière contre les fausses informations.

Lorsqu'une langue exige de rattacher grammaticalement les ouï-dire, la désinformation se propage plus lentement. On ne peut présenter une rumeur comme une vérité absolue car la grammaire elle-même indique qu'il s'agit d'un discours rapporté.

Cela favorise une culture de grande vigilance épistémique. Les auditeurs sont constamment conscients de la source de l'information, et les orateurs font preuve d'une prudence systématique pour éviter de surestimer leur certitude ou leurs connaissances.

En comparaison, l'anglais autorise les affirmations « sans marque grammaticale ». On peut retweeter un titre ou répéter une information sans qu'aucun marqueur grammatical n'indique l'absence de preuve directe de l'événement.

Adopter une approche fondée sur la preuve pourrait améliorer notre culture numérique. Même si notre grammaire ne l'exige pas, se demander « comment le sais-je ? » est une compétence moderne essentielle.

+ Monstres polysynthétiques : des langages qui regroupent des phrases entières dans un mot

Quel est l'impact de la notion de preuve sur la confiance sociale ?

La confiance au sein de ces communautés repose sur l'utilisation correcte de ces suffixes. Quiconque fait systématiquement un usage abusif de ce marqueur visuel, faute de connaissances de seconde main, est rapidement ostracisé.

Cette caractéristique linguistique agit comme un régulateur social. Elle décourage l'exagération et oblige les membres de la communauté à être précis quant à leurs expériences et aux limites de leur propre perception.

Les anthropologues ont constaté que cela donne lieu à une forme de conversation unique. Les débats sur « ce qui s'est passé » sont souvent résolus par l'analyse des indices probants utilisés par les témoins.

Cela modifie également la manière dont les histoires sont racontées aux enfants. Les récits établissent une distinction claire entre les mythes (rapportés/supposés) et les événements historiques (témoins des ancêtres), préservant ainsi l'intégrité des traditions orales.

Dès lors, la grammaire devient un code de déontologie. Parler correctement, c'est dire la vérité ; parler négligemment, c'est faillir aux règles les plus élémentaires du langage.

Quand les anglophones utilisent-ils ce genre de stratégies ?

Bien que l'anglais ne possède pas de règles grammaticales d'évidentialité, nous utilisons des stratégies lexicales pour parvenir à des résultats similaires. Nous nous appuyons sur des verbes de perception et des adverbes spécifiques pour signaler notre degré de certitude dans une affirmation.

Les avocats et les journalistes sont formés à utiliser ces marqueurs distinctifs. Un journaliste consciencieux écrit : « La police déclare que le suspect a pris la fuite », recourant ainsi à une stratégie de preuve indirecte pour attribuer cette affirmation.

Cependant, dans les conversations courantes en anglais, ces marqueurs sont souvent omis. Nous avons tendance à privilégier la concision à la précision épistémique, ce qui entraîne une prolifération rapide de malentendus et d'affirmations exagérées.

Nous utilisons également l'intonation et l'accentuation pour exprimer le doute. Un ton sarcastique peut servir de marqueur d'incrédulité, bien qu'il soit beaucoup moins fiable qu'un suffixe grammatical obligatoire.

Les linguistes affirment que les anglophones pourraient tirer profit de l'étude de ces systèmes. Comprendre comment d'autres cultures encodent la vérité nous incite à être plus attentifs au choix de nos mots.

Conclusion

Notre façon de parler façonne notre rapport à la vérité. Pour les locuteurs du tuyuca et du tariana, l'exactitude n'est pas une option ; c'est une exigence grammaticale inhérente à toute interaction.

Ces langues nous rappellent que toute information a une source. En reconnaissant d'où proviennent nos connaissances, nous respectons l'interlocuteur et préservons l'intégrité des faits que nous partageons.

Nous n’avons peut-être pas de suffixes obligatoires, mais nous pouvons adopter cette approche. Dans un monde complexe, prendre le temps de vérifier ses sources est l’acte ultime de responsabilité linguistique.

FAQ (Foire aux questions)

Quel est le langage le plus difficile en matière de preuve ?

Tuyuca est largement considérée comme l'une des plus complexes. Elle exige des locuteurs qu'ils classent les preuves en cinq types distincts pour chaque énoncé, ce qui rend sa maîtrise difficile pour les apprenants adultes.

L'anglais possède-t-il une grammaire probatoire ?

Non, l'anglais ne possède pas d'évidentialité grammaticale. Nous utilisons une évidentialité « lexicale », c'est-à-dire que nous ajoutons des mots distincts comme « allegagedly » ou « I saw » plutôt que de modifier la terminaison du verbe lui-même.

La preuve peut-elle empêcher de mentir ?

Cela rend le mensonge plus difficile sur le plan cognitif, mais pas impossible. Un locuteur peut toujours choisir d'utiliser faussement le suffixe « visuel », mais cela est considéré comme une grave transgression culturelle et linguistique.

Toutes les langues amazoniennes utilisent-elles ce système ?

Ce n'est pas le cas pour toutes les langues, mais c'est une caractéristique fréquente en Amazonie. De nombreuses langues de la région du Vaupés, quelle que soit leur famille linguistique, partagent ces traits en raison de contacts culturels de longue durée.

Comment les enfants apprennent-ils ces règles complexes ?

Les enfants acquièrent ces suffixes naturellement par immersion. Vers l'âge de quatre ou cinq ans, la plupart des enfants de ces communautés savent utiliser correctement les marqueurs évidentiels de base dans leur langage courant.

Ce concept est-il utile pour l'alphabétisation numérique ?

Absolument. Appliquer la logique de la preuve — toujours se demander « quelle est la source ? » — est une compétence essentielle pour naviguer sur les réseaux sociaux et éviter la diffusion d'informations non vérifiées.