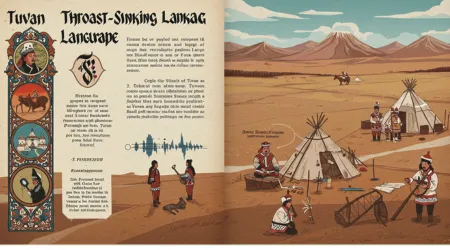

A língua cantada gutural Tuvan e sua paisagem sonora cultural

Língua de canto gutural Tuvan é mais do que uma técnica vocal — é uma expressão multidimensional de cultura, ambiente e identidade.

Anúncios

Enraizada nas tradições espirituais e sonoras do povo Tuvan, no sul da Sibéria, essa forma de canto harmônico transforma a voz humana em uma ponte entre a natureza e a comunicação.

Em uma época em que a diversidade linguística está diminuindo rapidamente, a sobrevivência e o reconhecimento global do khoomei são uma prova do poder da preservação cultural e da narrativa acústica.

Resumo

Neste artigo, exploraremos:

- A base histórica e cultural do canto gutural tuvano

- Seus elementos linguísticos e como eles a qualificam como uma “língua”

- Conexões entre som, identidade e harmonia ecológica

- Sua jornada pela modernidade e renascimento digital

- A linha tênue entre globalização e apropriação cultural

- Um olhar mais profundo sobre como essa tradição única está moldando as narrativas modernas

Quando a linguagem ressoa com a terra

O Língua de canto gutural Tuvan não surge de sistemas alfabéticos, mas da ressonância de montanhas, rios e do peito humano.

Anúncios

Conhecido localmente como Khoomei, essa prática antiga permite que um único cantor produza dois ou mais tons simultaneamente, criando um efeito que é melódico e hipnótico.

Historicamente, a técnica evoluiu como uma forma de os pastores se comunicarem em espaços vastos e abertos e imitarem o mundo natural que habitam.

Os sons ondulantes do vento, dos pássaros e dos corpos d'água não são apenas inspiração — eles são modelos.

Dessa forma, a própria paisagem se torna uma espécie de gramática, guiando a forma e a intenção do som.

Essas músicas não são compostas no sentido ocidental. Em vez disso, são improvisadas, reagindo a sons do ambiente e estados emocionais.

Um pastor sozinho a cavalo pode executar um som agudo sygyt para chamar animais distantes, ou um profundo kargyraa para evocar uma sensação de aterramento e presença.

Cada tom, altura e ritmo contém significado, mesmo sem palavras.

Leia também: Presságios de pássaros: o que significa quando pássaros cruzam seu caminho

Sons Ancestrais, Raízes Espirituais

Profundamente conectado ao xamanismo e ao animismo, o khoomei era tradicionalmente usado em rituais para se alinhar aos espíritos da natureza.

O sistema espiritual de Tuva vê o ambiente como vivo e comunicativo, e Língua de canto gutural Tuvan torna-se um meio para interagir com essas forças.

Em cerimônias, o canto gutural invoca rios, ecos de ancestrais ou o som de cascos galopando que levam mensagens ao divino.

Notavelmente, a estrutura sonora reflete esse propósito metafísico.

De acordo com uma pesquisa da Instituto Max Planck de Estética Empírica, o canto gutural utiliza tons harmônicos de maneiras que estimulam respostas cerebrais únicas, produzindo sensações que os ouvintes frequentemente descrevem como "meditativas" ou "transcendentes".

Esta forma de cantar não é apenas emocional — é somática. A sensação física de produzir harmônicos por meio da respiração e vibração controladas torna-se uma experiência de corpo inteiro.

Os praticantes descrevem isso como “sentir a terra se movendo através dos seus ossos”.

+ Koro: Uma língua oculta descoberta nas montanhas da Índia

Linguística Além das Palavras

Embora não contenha vocabulário ou sintaxe no sentido tradicional, o Língua de canto gutural Tuvan possui atributos linguísticos.

De acordo com o foneticista Dr. Ian Cross, sua manipulação de sobretons e sequência rítmica cumprem funções comunicativas equivalentes às linguagens verbais.

Assim como as línguas tonais (por exemplo, mandarim ou iorubá) usam o tom para diferenciar significados, o khoomei usa a estrutura tonal para sugerir mensagens, humor e até mesmo pistas baseadas em localização.

Vale ressaltar que o Khoomei é frequentemente executado com gestos, movimentos de cabeça ou orientação espacial que contextualizam ainda mais seu significado.

Essa natureza multimodal reforça seu papel como linguagem cultural. Em essência, o khoomei é "falado" tanto com o corpo e o ambiente quanto com as cordas vocais.

A interação de som e simbolismo é semelhante à forma como as línguas de sinais usam pistas visuais e espaciais.

Isso levanta uma questão retórica: se as línguas de sinais são reconhecidas como sistemas linguísticos completos, sistemas sonoros como o khoomei não deveriam receber o mesmo respeito?

Leia também: Vozes Indígenas: A Batalha para Salvar as Línguas Nativas

Reavivamento por meio da resistência e da redescoberta

Durante o regime soviético, práticas indígenas como o khoomei eram consideradas retrógradas ou até mesmo subversivas.

A música tradicional foi suprimida e a assimilação da língua russa foi promovida agressivamente. Mas a identidade cultural se mostrou mais resiliente do que a política autoritária.

Após a queda da União Soviética, houve um despertar nacional e espiritual em Tuva. Khoomei estava no centro disso.

A formação de grupos musicais como Huun-Huur-Tu e Chirgilchin ajudou a impulsionar o canto gutural tuvano para os holofotes internacionais.

Suas turnês globais nas décadas de 1990 e início de 2000 mostraram uma arte profundamente enraizada que podia transcender fronteiras sem perder a autenticidade.

Hoje, suas gravações são usadas não apenas em concertos, mas também em ambientes acadêmicos para ensinar acústica e etnomusicologia.

De acordo com um relatório de 2023 UNESCO relatório, o canto gutural tuvano foi designado como uma “herança oral e intangível criticamente significativa”, e esforços foram feitos para digitalizar gravações raras de meados do século XX.

Um esforço de arquivo notável é liderado por Instituição Smithsoniana, que abriga dezenas de gravações de khoomei acessíveis para educação e preservação.

Dados falam: Khoomei em números

Estima-se que 50.000 pessoas pratiquem ativamente alguma forma de khoomei em Tuva atualmente.

De acordo com o Projeto Línguas Ameaçadas, que representa quase metade da população masculina adulta — uma estatística notável diante da extinção linguística global, que dizima uma língua a cada 40 dias.

Entretanto, fora de Tuva, cerca de 30.000 praticantes e entusiastas estão espalhados pela Europa, Leste Asiático e América do Norte.

Programas de etnomusicologia em universidades como a UCLA e a Universidade de Viena agora incluem khoomei em seus programas, uma mudança significativa em relação a uma década atrás.

Paisagens Sonoras Digitais e Preservação por IA

O renascimento digital não deixou o khoomei para trás. Em plataformas como TikTok e YouTube, uma nova geração de artistas tuvanos está dando vida a canções tradicionais com visuais modernos e experimentação entre gêneros.

Ferramentas de IA também estão sendo implantadas para mapear e preservar padrões de canto gutural antes que sejam perdidos.

Em uma colaboração de pesquisa de 2024 entre o Ministério da Cultura de Tuva e o Media Lab do MIT, o aprendizado de máquina foi usado para analisar centenas de amostras de khoomei, catalogando estruturas tonais e vinculando-as a sons ecológicos específicos, como lobos uivando ou água borbulhando em riachos de montanha.

Isso não apenas afirma a reivindicação sônico-linguística, mas também estabelece as bases para a síntese de IA musical intercultural sem apagamento.

Ainda assim, há um equilíbrio delicado entre inovação e integridade. Quando produtores ocidentais usam khoomei em faixas de techno ou videogames, isso levanta preocupações sobre apropriação cultural indevida.

A questão não é o uso, mas o contexto, o crédito e a compensação.

Diplomacia Sônica e Significado Global

Curiosamente, o Língua de canto gutural Tuvan tornou-se uma forma de poder suave e diplomacia.

Em 2023, durante uma cúpula cultural da ONU em Genebra, a artista tuvana Aidysmaa Koshkendey se apresentou ao vivo, representando não apenas Tuva, mas a importância das linguagens baseadas em sons e da cultura ecológica.

Sua performance foi descrita pelos delegados como "visceral" e "intraduzível" — um lembrete de que algumas formas de expressão humana não podem, e não devem, ser simplificadas em alfabeto ou algoritmo.

Nesse sentido, o khoomei serve a um propósito global. É uma refutação viva da ideia de que apenas as línguas escritas ou faladas têm valor.

E em uma era de crise climática, sua sintonia ambiental se torna não apenas poética, mas instrutiva.

Analogias e Ecos

Para descrever o Língua de canto gutural Tuvan para alguém que não conhece é como descrever caligrafia para alguém que só digitou fontes.

Não se trata apenas de entregar informações, mas sim de como essa entrega é texturizada, sentida e vivenciada.

Khoomei é uma forma audível de contar histórias por meio de arquitetura sonora.

Também é profundamente analógico em um mundo digital. Enquanto muitas culturas se apressam em automatizar a linguagem por meio de previsão de texto e chatbots, o khoomei insiste em presença, respiração e intenção.

Não dá para fingir cantar guturalmente. É preciso sentir — e isso por si só já é um ato radical.

Perguntas frequentes

O que exatamente é a língua de canto gutural dos Tuvan?

É uma forma sonora de expressão cultural em que sobretons são usados para comunicar significado e nuances emocionais. É não verbal, mas carrega a estrutura e a intenção de um sistema linguístico.

É praticado apenas por homens?

Tradicionalmente sim, mas as mulheres têm aderido cada vez mais à prática. Artistas modernos como Sainkho Namtchylak ajudaram a quebrar esses tabus.

Pode ser aprendido por pessoas de outras nacionalidades?

Com certeza. Embora o contexto cultural seja essencial, as técnicas vocais podem ser ensinadas e praticadas globalmente — com respeito e orientação adequada.

É reconhecido oficialmente como uma língua?

Ainda não no sentido jurídico-linguístico, mas linguistas e preservacionistas culturais argumentam cada vez mais que deveria ser.

Onde posso ouvir gravações autênticas?

Visite o Coleção Smithsonian Folkways, que abriga um rico arquivo de apresentações de canto gutural tuvano com contexto cultural completo.